Into me, into you, into sky-lit nights we folded and pushed into our pockets. Thoughts untie, days press on. The grass is flattened from where we were lying—where we are lying now and always. Mercy of the sun and shadow of the wind—how should I go on? It depends on how I listen, how we will fall into one another later. Not knowing how to slip out and under, how to take a year back beneath the wings I do not have and send words into the air. Begin with the end. Circle around, follow footsteps back. When you are beside me again, our hearts will sing, in silence, in the shadow of the wind.

*

Time disquiets; nature prevails. We try to find control in various ways. Sometimes we work with nature and time; sometimes we work against them. No matter how much we think we decide or control, we will always be slaves to memory and history.

That said, what is there we can actually do? How might we choose to navigate through all of this? Actions are breathed in through the body and exhaled as art—as poetry, paintings, sculptures; as sweaters knit, or songs played on the piano. It is not always art in its conventional sense, but we must do something to create, or else experiences continue passing, both slowly and rapidly, and we have nothing to show for them. At least we might make the bed in the morning, or send a letter to an old friend. That might be something that helps us express ourselves, convey something in a tangible way. It seems you can hold a dream in your hand if you write it down; you can touch a vision if you take a photograph. Still, these are altered versions of first-hand experience. We’ll never quite be able to impart what we felt at the time.

Just like places or interactions, objects alone evoke certain emotions, associations. A cup of coffee or the way the sun falls onto the floor through the windows: these things are not sipped or viewed detachedly. They are felt in a basic as well as an ethereal way, assuming we are open to those feelings. What service can an inanimate object render, if the human does not give it meaning in his or her own life? How do we place the feelings these objects evoke onto a page, a canvas? The artist takes in experiences, processes them, and then creates. This is meant to be fluid movement, not a series of compartmentalized actions. He or she displays what is important to him or her, whether found or created. We may not agree with what they find to be of significance or beauty. Then again, a flower cannot hope to mean anything to anyone who does not care to kneel down and observe its form, take in its scent, analyze its shape. Maybe anything we study for long enough becomes of certain importance and beauty. When we put together the precepts “know thyself” and “study nature,” we realize that these factors are inextricable. Studying the natural procession of things, we figure out who we are and where we fit into all of it. We realize what we want to create, how we want to create it.

*

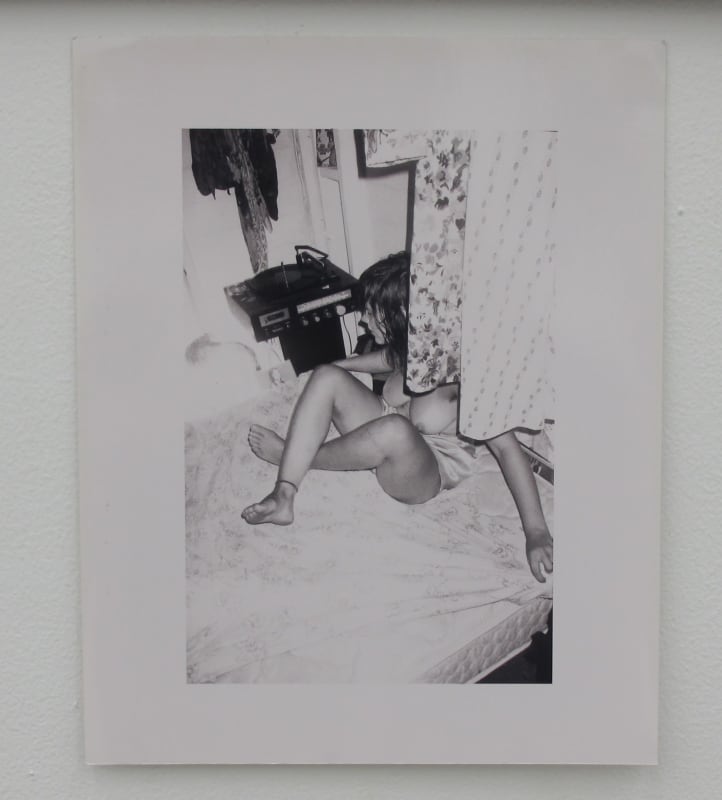

Ryan Foerster utilizes nature in a way that is unique when we consider the typical association of nature-related art. He does not paint epic landscapes from the tops of mountains or tack deerskin to the wall. Working mainly within the realm of photography, he does several things, either altogether or one at a time: he incorporates nature into his work, lets nature destroy/alter/improve his pictures, and creates the initial images from nature (as when he puts unexposed sheets of photo paper outside). He does not ask for a certain picture to be made, yet he always gets an answer. Elements like water, wind, and dirt work together to alter whatever Ryan gives them. It is neither entirely Ryan nor entirely nature that completes such works, but a balance of the two.

Ryan reminds us of everything that never was and everything that could have been. He lets a piece of art take a different course than another artist might. At a point where one might think something is complete, Ryan might add another step to the process. Similarly, something that looks raw and unfinished—not yet painted on, not yet finalized—might be exactly what Ryan wants.

Tangled into the images he shows are the ideas of presence and absence, love and longing, dates of expiry and of birth. Did he find this on the street or make it himself? A discarded object may come to life again when Ryan discovers it, takes it home, and places it in a new context—thereby giving it purpose where it otherwise may have become valueless.

Has this been said before? Maybe. But it is important to reiterate these processes, understand how all of it evolves to be what it finally is. When it all comes together as a unified piece or a complete show, the steps taken cannot be seen. It was once real and cluttered and alive. Hopefully, some of these factors can still be felt when the art is mounted or otherwise placed within the confines of a gallery.

*

Is it strange that I’ve written this? Sometimes I think so. But I don’t want to feel that I can’t express these things on a more public level just because I am romantically involved with the artist. After all, I do know the most about the photo paper on the ground covered in lemons that I just squeezed and jars from olives we ate for lunch—though oftentimes I am surprised by pieces I nearly step on or that I notice in the window after a couple of mornings. And as I began to write about time and nature in a general way, I realized how much it related to Ryan’s ideas and processes, so I continued writing until you were able to hold this in your hands.

hannah buonaguro

October 2012

*

Time disquiets; nature prevails. We try to find control in various ways. Sometimes we work with nature and time; sometimes we work against them. No matter how much we think we decide or control, we will always be slaves to memory and history.

That said, what is there we can actually do? How might we choose to navigate through all of this? Actions are breathed in through the body and exhaled as art—as poetry, paintings, sculptures; as sweaters knit, or songs played on the piano. It is not always art in its conventional sense, but we must do something to create, or else experiences continue passing, both slowly and rapidly, and we have nothing to show for them. At least we might make the bed in the morning, or send a letter to an old friend. That might be something that helps us express ourselves, convey something in a tangible way. It seems you can hold a dream in your hand if you write it down; you can touch a vision if you take a photograph. Still, these are altered versions of first-hand experience. We’ll never quite be able to impart what we felt at the time.

Just like places or interactions, objects alone evoke certain emotions, associations. A cup of coffee or the way the sun falls onto the floor through the windows: these things are not sipped or viewed detachedly. They are felt in a basic as well as an ethereal way, assuming we are open to those feelings. What service can an inanimate object render, if the human does not give it meaning in his or her own life? How do we place the feelings these objects evoke onto a page, a canvas? The artist takes in experiences, processes them, and then creates. This is meant to be fluid movement, not a series of compartmentalized actions. He or she displays what is important to him or her, whether found or created. We may not agree with what they find to be of significance or beauty. Then again, a flower cannot hope to mean anything to anyone who does not care to kneel down and observe its form, take in its scent, analyze its shape. Maybe anything we study for long enough becomes of certain importance and beauty. When we put together the precepts “know thyself” and “study nature,” we realize that these factors are inextricable. Studying the natural procession of things, we figure out who we are and where we fit into all of it. We realize what we want to create, how we want to create it.

*

Ryan Foerster utilizes nature in a way that is unique when we consider the typical association of nature-related art. He does not paint epic landscapes from the tops of mountains or tack deerskin to the wall. Working mainly within the realm of photography, he does several things, either altogether or one at a time: he incorporates nature into his work, lets nature destroy/alter/improve his pictures, and creates the initial images from nature (as when he puts unexposed sheets of photo paper outside). He does not ask for a certain picture to be made, yet he always gets an answer. Elements like water, wind, and dirt work together to alter whatever Ryan gives them. It is neither entirely Ryan nor entirely nature that completes such works, but a balance of the two.

Ryan reminds us of everything that never was and everything that could have been. He lets a piece of art take a different course than another artist might. At a point where one might think something is complete, Ryan might add another step to the process. Similarly, something that looks raw and unfinished—not yet painted on, not yet finalized—might be exactly what Ryan wants.

Tangled into the images he shows are the ideas of presence and absence, love and longing, dates of expiry and of birth. Did he find this on the street or make it himself? A discarded object may come to life again when Ryan discovers it, takes it home, and places it in a new context—thereby giving it purpose where it otherwise may have become valueless.

Has this been said before? Maybe. But it is important to reiterate these processes, understand how all of it evolves to be what it finally is. When it all comes together as a unified piece or a complete show, the steps taken cannot be seen. It was once real and cluttered and alive. Hopefully, some of these factors can still be felt when the art is mounted or otherwise placed within the confines of a gallery.

*

Is it strange that I’ve written this? Sometimes I think so. But I don’t want to feel that I can’t express these things on a more public level just because I am romantically involved with the artist. After all, I do know the most about the photo paper on the ground covered in lemons that I just squeezed and jars from olives we ate for lunch—though oftentimes I am surprised by pieces I nearly step on or that I notice in the window after a couple of mornings. And as I began to write about time and nature in a general way, I realized how much it related to Ryan’s ideas and processes, so I continued writing until you were able to hold this in your hands.

hannah buonaguro

October 2012