Martos Gallery is pleased to present the first survey exhibition of German artist Hans-Jörg Mayer in New York, organized in collaboration with Galerie Nagel Draxler. Featuring paintings spanning three decades, the exhibition will be on view from November 2, 2023 to January 6, 2024.

Hans-Jörg Mayer has continually conceived of art history in his own terms, working through its contents using his own tools. He maintains the romanticism of old masters, while repeating the benefits of modernism. For Mayer, god is Andy Warhol, goddess Isa Genzken. Edvard Munch also maintains a seat at the table.

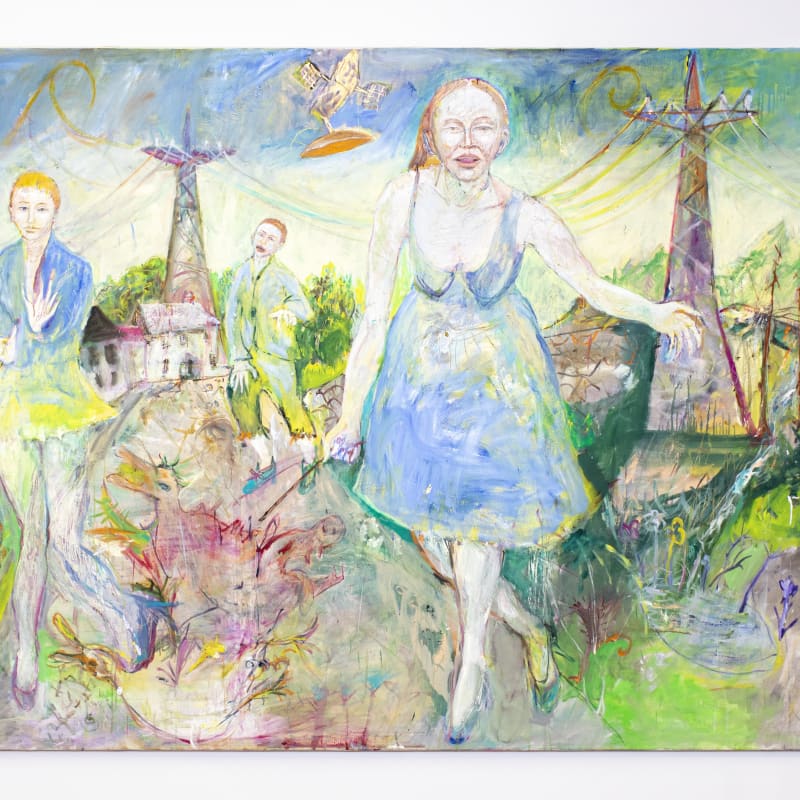

In keeping with a Pop Art edict, Mayer’s content is largely plucked from cultural objects such as magazines, photographs, cinema, pop songs, advertisements, and the internet. The artist, however, largely elides any static, genre-based authoritarianism. His arsenal of forms and gestures is alternatively mediated by an inner register bent toward expressive brushwork and an earnest disposition, resistant as he is to external directives. Mayer consequently operates between flow state and a lucid awareness of his medium and application.

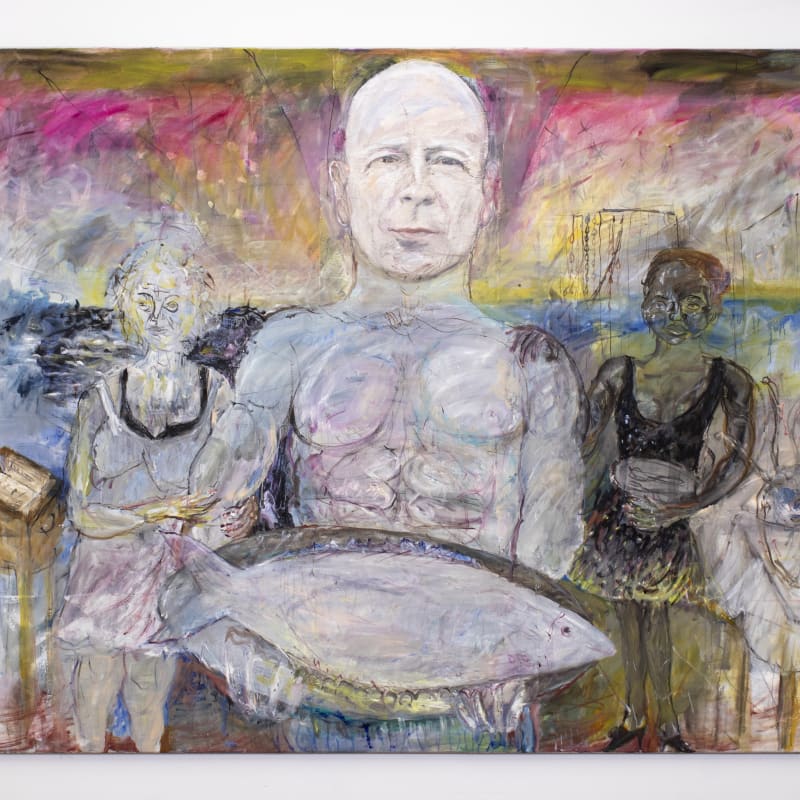

In a painting like Hänsel und Gretel, he conjures the energies of El Greco; Todos los Santos bears the residues of Max Beckmann’s discomfiting portraiture; The sinuous lines and supine bodies of Dreamers encroach upon Egon Schiele’s aesthetic territory. Christian iconography is also manifest in Mistral, with Bruce Willis at the fore, clutching a fish whose simplistic delineation resembles that of the ichthys. Mayer has been cast as the dramaturg of these peopled scenes. These other worlds that he’s built have direct tethers to our material one, with recognizable objects and conditions cavorting through bewitched landscapes.

The passage of time for Mayer means less information laid out on canvas, and his newer images see the painter challenging perspective by way of white backgrounds, which inevitably complicate space. He often doubles down on a theme, producing series revolving around butterflies, disco balls, clowns, and spiderwebs. Notability, Mayer’s floral paintings contain his knowledge without its overt revelation. These paintings aren’t about history, instead they implicate it naturally as its weight is undeniable within the medium.

In speaking of his renderings of tulips, he briefly mentions the bulbs’ price spike in seventeenth century Holland, though admits that this is merely a sideline concern of his. This motif truthfully emerged during a Berlin winter, when the artist’s disgust toward painting was dashed by a chance encounter with small green blossoming flowers printed in a newspaper. He was moved to visit a local florist who, at that moment, only carried tulips. While he was originally unimpressed by this particular genus, he came to appreciate the tulips’ presence in his home. While recognizing their quotidian nature, Mayer nonetheless submitted to the subject.

Just as his tulips bleed, Mayer’s sunflowers slowly lose their vibrancy. These flora operate as memento mori, despite their initial affirmations of life. Likewise, Mayer’s desire to paint sympathetic zombies recapitulates this friction between death and non-death.

Hans-Jörg Mayer has continually conceived of art history in his own terms, working through its contents using his own tools. He maintains the romanticism of old masters, while repeating the benefits of modernism. For Mayer, god is Andy Warhol, goddess Isa Genzken. Edvard Munch also maintains a seat at the table.

In keeping with a Pop Art edict, Mayer’s content is largely plucked from cultural objects such as magazines, photographs, cinema, pop songs, advertisements, and the internet. The artist, however, largely elides any static, genre-based authoritarianism. His arsenal of forms and gestures is alternatively mediated by an inner register bent toward expressive brushwork and an earnest disposition, resistant as he is to external directives. Mayer consequently operates between flow state and a lucid awareness of his medium and application.

In a painting like Hänsel und Gretel, he conjures the energies of El Greco; Todos los Santos bears the residues of Max Beckmann’s discomfiting portraiture; The sinuous lines and supine bodies of Dreamers encroach upon Egon Schiele’s aesthetic territory. Christian iconography is also manifest in Mistral, with Bruce Willis at the fore, clutching a fish whose simplistic delineation resembles that of the ichthys. Mayer has been cast as the dramaturg of these peopled scenes. These other worlds that he’s built have direct tethers to our material one, with recognizable objects and conditions cavorting through bewitched landscapes.

The passage of time for Mayer means less information laid out on canvas, and his newer images see the painter challenging perspective by way of white backgrounds, which inevitably complicate space. He often doubles down on a theme, producing series revolving around butterflies, disco balls, clowns, and spiderwebs. Notability, Mayer’s floral paintings contain his knowledge without its overt revelation. These paintings aren’t about history, instead they implicate it naturally as its weight is undeniable within the medium.

In speaking of his renderings of tulips, he briefly mentions the bulbs’ price spike in seventeenth century Holland, though admits that this is merely a sideline concern of his. This motif truthfully emerged during a Berlin winter, when the artist’s disgust toward painting was dashed by a chance encounter with small green blossoming flowers printed in a newspaper. He was moved to visit a local florist who, at that moment, only carried tulips. While he was originally unimpressed by this particular genus, he came to appreciate the tulips’ presence in his home. While recognizing their quotidian nature, Mayer nonetheless submitted to the subject.

Just as his tulips bleed, Mayer’s sunflowers slowly lose their vibrancy. These flora operate as memento mori, despite their initial affirmations of life. Likewise, Mayer’s desire to paint sympathetic zombies recapitulates this friction between death and non-death.