The Collective comprises seven artists who center criminal justice reform in their practices, aligned by their shared experiences of incarceration, and their commitment to supporting artists who have overcome similar backgrounds. The Collective began with Jared Owens commandeering a small recreation room at FCI Fairton Correctional Facility, New Jersey, as an art studio, where he met fellow artists Jesse Krimes and Gilberto Rivera. A bond was quickly formed, ideas were traded, and a pact was made to continue their art careers upon coming home. Since 2014, the collective has grown to include Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter aka Isis Tha Saviour, Tameca Cole, Russell Craig, and James “Yaya” Hough, artists who had formed their own connections during their respective incarcerations, and who find themselves now committed to changing how society views formerly incarcerated artists, a theme that permeates all their work.

Through the artists’ collaborations, they have founded supportive platforms such as the Right of Return Fellowship, cofounded by Jesse Krimes and Russell Craig, as well as garnering encouragement and advocacy from Agnes Gund’s Art for Justice Fund at the Ford Foundation. The work of Dr. Nicole R. Fleetwood—including her decade of research; her seminal book, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration; and the 2020/2021 MoMA PS1 exhibition—further established these artists and expanded their network. Now, as each artist builds their career independently, they remain bonded through the mutual experiences of incarceration and, more significantly, determination: one another’s Chosen Family.

Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter began at an early age to emulate and study Isis, the Egyptian goddess of healing and motherhood, an alignment cemented when the artist underwent the traumatic experience of giving birth while incarcerated. Officially adopting Isis Tha Saviour as her alter ego, Baxter went on to raise her son while becoming a successful hip hop artist, whose music videos are celebrated in the fields of entertainment and fine art alike. On view at Martos is Fall of America (2020), in which Baxter collages historical and contemporary footage of oppression and uprising, police violence and protest—a three-minute montage of the conditions that have perpetuated from slavery to lead to our current, simmering moment. Baxter’s rap similarly enumerates the systemic injustices that threaten the country’s cohesion. In a quiet, yet similarly urgent departure, Baxter performs a poignant embodiment of Isis in Consecration to Mary (2021) a series of intimately scaled tin type cases. Following her research into Thomas Eakin’s exploitative photograph of an anonymous, pre-pubescent black girl posed nude, Baxter created a series of photos inserting her own, protective presence over the exposed child, covering the girl’s body, and rescuing her from isolation.

Tameca Cole’s works on paper harness the range of portrayals of black bodies in the media, her composites alternately redemptive, cathartic, meditative and celebratory. At times, as in Open Wounds (2021) the technique of collage serves to compress history and emphasize the historical continuity of racial violence. In Open Wounds, atop a roiling, charcoal ground, Cole applies a hand ripped collage of the infamous image known as “Whipped Peter,” the Civil War era photograph of a

formerly enslaved black man, who stoically turns his back to the camera to reveal excessive keloid scarring on his back from whipping. Peter’s head is represented by a silhouette, over which Cole has affixed with the eyes of Tupac Shakur, his right hand clasping a microphone in performance. Eliding two famous portrayals of black men in the media, Cole captures several contradictions—the appreciation of black culture amidst the ignorance of black pain; the power of mass media to galvanize as well as fetishize; and the various guises of oppression (Shakur’s fame and success were beset by police brutality, incarceration, and gun violence, which tragically ended his life). Also on view is Asexual Accessories, a seductive, large scale collage that isolates erogenous features—lips, abs, feet placed next to a phallic abstraction—alongside the luxury signifier of quilted Gucci patterning, applied through graphite rubbing and grafted collage. Equating infatuation with superfluity, Cole’s alluring work ultimately telegraphs how deeper bonds elude surface representation.

Russell Craig illuminates painful histories and startling political realities through the deployment of pop culture narratives, his references ranging from Marvel comics to The Wizard of Oz. Real Fake (2021) is painted on a surface of luxury bags, both in knockoff and authentic form. A section of the surface is peeled away to reveal a rough patch of white. Tethered to this peeling patch is a small toy dog—recalling the moment in The Wizard of Ozwhere Toto pulls back the curtain to reveal an old man in a booth, operating the illusion of Oz with gears and levers. With this gesture, Craig connects power, optics, and race. To further demonstrate this triadic relationship, Craig paints his warped and horrified self-portrait into the helmet of Marvel’s Mysterio: a supervillain from the Spiderman comics, whose powers are derived from his ability to generate thoroughly convincing mirages and destabilize the hero’s reality.

Using banal, administrative material to showcase the benign tools of insidious penal codes, James “Yaya” Hough’s darkly satirical drawings literalize the for-profit prison industrial complex. In Hough’s drawings, uniform and featureless bodies are fed through machinery, bound up in rope, their anatomy captured in systems of production, consumption, and even sexual humiliation, sometimes at the hands of a recurring, voluptuous female character. Hough draws in ballpoint pen, on bureaucratic paperwork that testify to the monotony of carceral time, including cafeteria menus and documents used to process an incarcerated person’s daily activities.

Jared Owens employs a symbology that describes the spatial conditions of incarceration, or what Nicole Fleetwood has described as “penal space,” using specific color and imagery to outline the unspoken methods through which prisons contain and control. Cadmium orange appears throughout Owens’ canvases, a bright color that demarcates restricted zones within the generally sedative, muted tones of prison (additionally, cadmium’s chemical flammability renders it contraband). Owens also correlates incarceration and slavery through an examination of architectural parallels, noting the similarities between the infamous Brookes slave ship imprints, and the layout of Fairton Correctional Facility, each designed to maximally constrain and objectify the populations they hold.

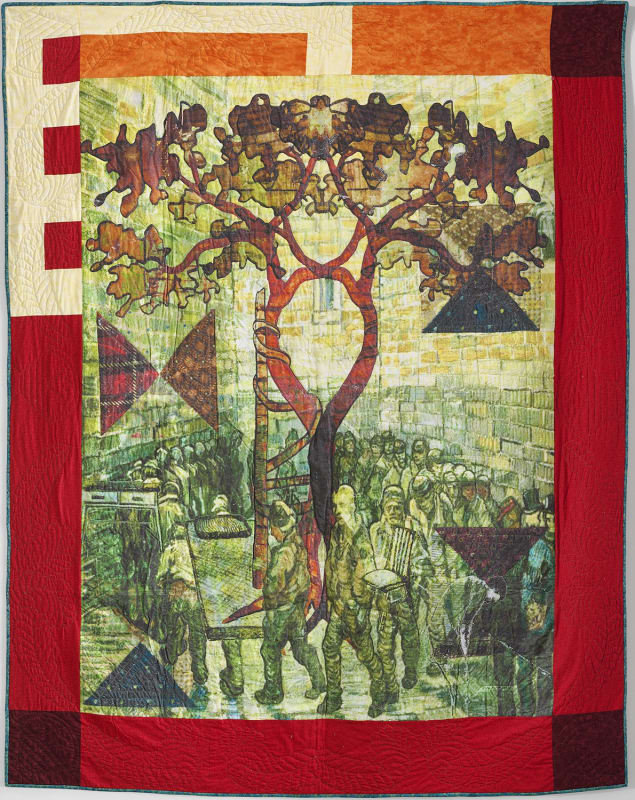

Quilts by Jesse Krimes symbolically suture the fractured constellation of sites that comprise penal space, interrogating ideas of justice, safety, time, community and return. Fleetwood reminds her reader in Marking Time that penal time is not only constituted by the architectural codes of prison itself, but also by the external locations impacted by incarceration. She describes homes which lose family members, their remaining members emotionally, financially, and spiritually depleted; as well as the relationship of carceral space to the broader public imaginary: the existence of prison itself is fixed by age old stereotypes, while actual facilities are isolated from the general population. Krimes’ quilts embody a process of co-creation and dialogue from both prison and non-incarcerated communities. In the works on view, Krimes integrates imagery produced by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, folding into the imagery further responses and reflections on social justice from people employed in the carceral system, as well as members of the Amish Mennonite faith in small town, central Pennsylvania. Krimes draws on regionally specific visual elements and techniques, which reference a shared social fabric and have personal resonance for the artist as a formerly incarcerated person with generations of family in Lancaster County, PA, where he was arrested, indicted, and sent to federal prison.

In Gilberto Rivera’s paintings, the artist wraps allegorical images of innocence and justice in swirls of loaded collage—Rivera’s imagery includes Puerto Rican civil rights leaders Pedro Albizu Campos, Lolita Lebrón, and Filiberto Ojeda Ríos; phrases both cautionary and hopeful; cell blocks and faces behind bars. Collectively, Rivera’s imagery reflects the centuries-long struggle sometimes referred to as the arc of justice. Rivera focuses on children and women as the subjects of his paintings, indicating that children witness, learn from and inherit the catastrophes of the present, and women often bear their emotional burden. (While women represent less than a tenth of the incarcerated population, they are also the fastest growing demographic in prisons, and many are incarcerated for acts committed in self-defense against domestic partners). This is America #002 is bisected by a painted strip of caution tape: above it, a young boy meditates amidst a churn of chaotic imagery; below, his pants are orange and his shoes laceless, signaling his risk of incarceration and overall the environmental factors that can funnel a child into the carceral system.

Together, the artists in The Collective: Chosen Family illuminate obscured histories, challenge dominant narratives, and practice passionate activism through their work, demonstrating the power of art to heal, educate, and galvanize.

—Katherine Siboni

Martos Gallery would like to extend our most sincere thanks to Dr. Nicole R. Fleetwood, for her kind generosity with her award-winning, decade-long, and highly personal project. Additionally, we are extremely grateful to the original MoMA PS1 team: Kate Fowle, Director, Josephine Graf, Curatorial Assistant; Jocelyn Miller, Former Assistant Curator, PS1; and Amy Rosenblum-Martín, Guest Assistant Curator. Without their respective curatorial gifts, as well as their expertise and coordination with Martos, our exhibition would not be possible. Additionally, Martos thanks Jared Owens, for his passionate advocacy for his peers and exceptional organizational support. Lastly, we extend our thanks to Stephanie Ingrassia and Dana Gluck of Spring Hill Arts Gathering, for their support of the Collective and kind coordination with Martos Gallery. Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration will travel to the Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts (AEIVA) at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, opening September 17 (through December 11, 2021).

The net proceeds to Martos Gallery from this exhibition will go toward a $10,000 donation toward The Felix Organization, which provides a wide range of opportunities and resources to broaden, enrich, and support the lives of children growing up in the foster care system. Cofounded in 2006 by fellow adoptees Sheila Jaffe and Darryl DMC Daniels, Felix provides camp programs, year-round extracurriculars, scholarship, holiday gift cards and much more to children in need on both coasts. Martos will also be making a $10,000 contribution to the Right of Return Fellowship. The Right of Return Fellowship, cofounded by Jesse Krimes and Russell Craig, and now in its fourth year, provides annual grants to formerly incarcerated artists who deal with issues of criminal justice reform in their work. Right of Return affords artists navigating reentry the resources to contribute their significant, firsthand experience to the critical dialogue surrounding social justice.

To donate to the Felix Organization: https://www.thefelixorganization.org/donate.

For more information on Right of Return, visit: https://www.rightofreturnusa.com.